For a habitual faith seeker, any journey to the State of Uttarakhand in Northern India is synonymous with a visit to the Char Dhams: the four Hindu pilgrimage centres of Kedarnath, Badrinath, Gangotri and Yamunotri. The westernmost of the Char Dhams, that is, Yamunotri is the source of the Yamuna River and the seat of the Goddess Yamuna, sister of Yama, the God of death.

The town of Barkot, the last urban centre on the way to Yamunotri is about 50 kilometres from it. Every summer in May and June, busloads of pilgrims descend on Barkot before progressing on their pilgrimage to Yamunotri and, over the years, this once-sleepy village has changed into a busy, bustling town. Gradual urbanisation has transformed agricultural fields into concrete ensembles and beautiful flowing streams have been polluted by urban waste. The majestic view of the Bunderpunch range – once visible from almost everywhere in Barkot – is now hidden by rows of concrete structures sporting fancy names like ‘Hotel Hill View’ and ‘Barkot Queen’.

But on the other side of Barkot, across the River Yamuna, life in the villages scattered across the undulating hills of the Rawai Valley have largely remained the same. Save a handful of modern amenities such as electricity and mobile phones, not much has changed here. Sunaldi is one such village. A casual visitor might dismiss it for just another sleepy, hilly hamlet, but a keen observer will note the striking top-heavy fortress-like miniature structure on the village fringe.

The structure has a somewhat unusual appearance for a village house. About four storeys high, the house showcases timber-faced stone walls crowned by a sloping roof and a projecting balcony at the uppermost level running all around the building.

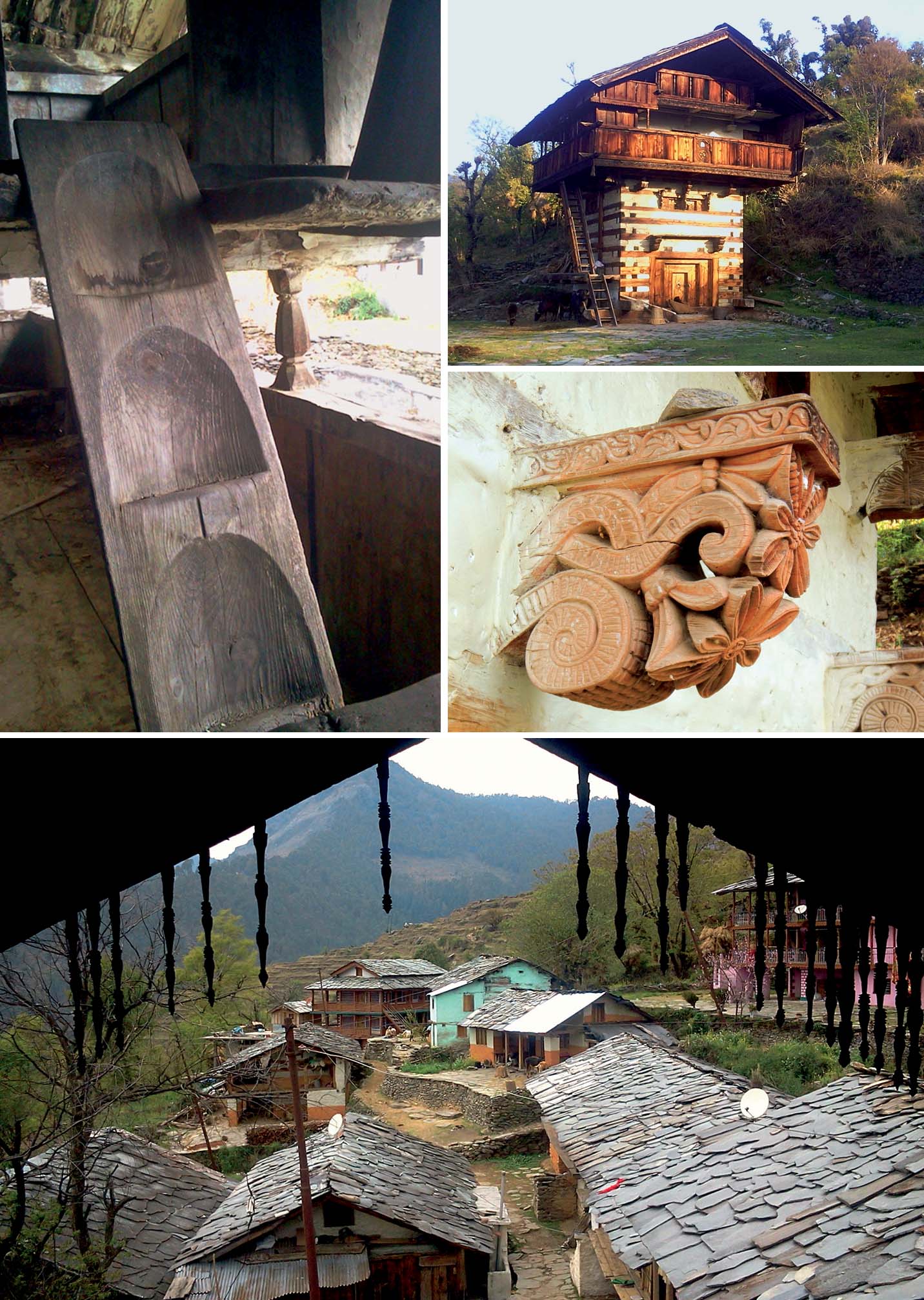

Bottom: Oldest pherol in the region in Koti Banal

The Pherol as a Dwelling Type

The entire Rawai Valley was once dotted with such multistorey structures, known as pherols in the local dialect. Originally conceived as a single-family unit, every floor has one room with a vertically distributed usage. The ground floor was used for cattle or grain storage. The upper floors were used as living and sleeping quarters. The kitchen used to be on the top floor. In some buildings, a crude form of toilet exists at the uppermost story with an outlet for drainage. It is generally located at the cantilevered rear part of the balcony.

The main construction materials used for these houses are stone and timber (mainly ‘deodhar’ or Cedrus deodara). The construction is essentially of timber-reinforced coarse-rubble masonry with mud mortar joint type. Similarities in the structural details of the pherols suggest their possible evolution under one single architectural school, the Koti Banal style of architecture named after the local village of Koti Banal in the Yamuna Valley where the first pherol came up about 800 years ago and exists even today.

The pherol’s fortress-like feature is attributed to security and self-defense needs. Wandering armies from adjoining Nepal used to invade the region. Similar threats existed from the Gurkhas of the British army during the colonial rule. The lone pherol in Sunaldi still bears bullet marks. As per local folklore, while the Gurkhas would lay siege to the structure for several weeks, they were unable to enter it. Camouflaged tunnels connected to a neighbouring water source ensured a continuous supply of potable water for the inhabitants of the pherol during this period.

Generally, pherols have a single main entrance just above the foundation platform. Access to the upper floors is through a detachable wooden ladder (carved from a tree trunk). When the ladder was withdrawn from above, the upper floors were completely inaccessible for the enemy even if they managed to break into the dwelling.

Top Right first: Modifications in pherol. Improved accessibility to upper floors with external staircase

Top Right second: Wood carving detail

Bottom: Koti Banal village view from a pherol. Note the RCC house in pink

Earthquake Resilience

The entire Himalayan region is earthquake-prone. During an earthquake, the combination of compression, tension and shear forces act in complex ways on the structure and its constituent elements, causing them to behave differently and independently of one another. When struck by an earthquake, the weaker elements may fail and lead to a domino effect, causing the failure of other elements and this increases the risk of overall failure of the structure. There is a need for earthquake-resistant or aseismic building design to prevent such failure. The design must ensure that the structure has adequate strength, high ductility and the ability to remain a single unit when subjected to large deformational forces.

Pherols are built as earthquake-resistant structures and have successfully withstood numerous earthquakes. Their structural style, somewhat similar to that of modern framed structures testifies to the unique skills and expertise of past generations who, despite any formal training, had understood the logic of earthquake engineering. There are several common features of seismic resistance identified in the pherols.

Most pherols have a simple rectangular plan and are constructed on a raised solid platform of dry stone masonry, which is a continuation of the foundation trench of rubble stones. This enhances the stability of the structures by keeping the centre of gravity of the entire building near the ground.

The pherol’s walls are made of layers of dry stone masonry alternating with wooden beams that traverse the entire length of the walls. The walls, ranging in thickness from 40 cm to over 100 cm, are usually composed of flat and long stones well laid to evenly distribute the compressive strain vertically and thwart the outward movement of stones in the wall. The wooden beams or tie-bands impart ductility to an otherwise brittle structure, helping the building to resist tension and lateral forces during an earthquake while transferring the inertial forces (forces due to the movement of the building as a whole) to the ground.

Pherols demonstrate that massive houses too can withstand earthquakes provided the necessary design and construction precautions are taken

To enhance strength, there is a need to tie the inner and the outer portions of the wall. A pair of timber beams is interconnected at regular intervals along the length of the wall with wooden pegs. This arrangement largely takes care of the sheer forces that develop during the earthquake.

Wooden blocks reinforce the corners of the outer walls. They help distribute the seismic loads vertically and also prevent the wall from splitting under high compressive force. The use of long flat stones, laid perpendicular to one another at the corners also enhances their strength. Within the building, diagonal braces help keep walls perpendicular and strengthen corners. The impeccable joinery reflects the skilled craftsmanship of local masons.

Though pherols are observed to have three, four (Chaukhat) to five (Panchapura) storeys, the floor height is low to keep the centre of gravity of the entire building close to the ground. This reduces the possibility of over-turning of the structure during an earthquake.

Doors and windows are of minimum dimensions to both augment insulation and more importantly for earthquake resistance by minimising weak links. The placement of openings is staggered and avoids vertical alignment, which would structurally weaken a wall. Heavy wooden reinforced frames help bear the accumulated stress on the openings during an earthquake.

Though lower mass and lower centres of gravity make a building less likely to topple over in an earthquake, pherols clearly demonstrate that massive houses too can withstand earthquakes provided the necessary design and construction precautions are taken.

Contemporary Condition

Pherols originated in a society where a co-operative form of living was the prevalent practice. Agriculture and construction of houses were a community initiative. The large size of pherols clearly suggests that it was the handiwork of an entire community.

Technology is a derivative of a society’s knowledge base. The last few decades have witnessed a massive out-migration of able-bodied and skilled people from the hills, largely due to lack of sustainable livelihood options. This has eroded the human resources and knowledge base of the hills. Simultaneously, aggressive and extensive promotion of cement-based construction by cement companies has caught the fancy of the locals. Shortage of traditional building materials like wood and stone has added to the problem. Many pherols lie abandoned and are in various stages of deterioration due to lack of maintenance. Some owners are even demolishing them voluntarily to reuse the building material for modern construction.

While reinforced cement construction (RCC) can be highly earthquake-resistant, the manner in which this new technology is being applied in the rural areas of the Himalayas raises several questions regarding its sustainability. One of the most publicised aspects of RCC construction is its rigidity and high compressive strength. However, the goal of seismic architecture is not to design buildings that do not fail, but to allow controlled failure to help dissipate the massive stresses experienced by a building during an earthquake. One of the problems of using cement in rural construction is that if the strength of the cement mortar exceeds the strength of mud bricks, the latter may break, even as the former resists the force. Eventually, the building collapses without any warning causing loss of life and property.

In a rural context, there are limits to the availability of appropriate construction materials as well as inadequate knowledge about the use of new-age technologies. Indigenous construction practices still have much to offer in terms of their inherent sustainability and appropriateness, as they have evolved through a time-tested wisdom of environmental constraints and empirical knowledge of the forces generated in an earthquake. For example, the construction of pherols intentionally uses weak mortar (lime in place of cement), loose in-fill walls and plaster that can shatter easily during an earthquake, thus helping in stress dissipation on the building.

If pherols are to be renovated for the purpose of homestays, they will need to be made more liveable with the help of modern technological interventions

The Pherol in Perspective

Existing pherols, some of which are as old as 800 years or so, need to be protected as heritage buildings. To avoid any damage to these structures, unplanned construction around them needs to be regulated by law. There is scope for promoting ecotourism in the region and the pherols may be converted into heritage homestays with suitable modifications and addition of basic amenities. Apart from generating employment opportunities for the local people, this will encourage them to preserve these traditional dwellings.

If pherols are to be renovated for the purpose of homestays, they will need to be made more liveable with the help of modern technological interventions, without altering the basic building fabric and elements of seismic-resistance. As noted earlier, the primary purpose of their construction was security with minimal consideration for the comfort of the inhabitants. Variations and modifications to the original style were undertaken as early as 300 years ago to improve the comfort and accessibility quotient. In some cases, the sizes of openings and the floor-to-ceiling height have been enhanced. In others, timber verandas resting on massive columns have been added for additional living space. A pherol in Koti Banal village has external wooden ladders for improved accessibility to the upper floors.

Changing outlooks as well as living patterns cannot be ignored. At the same time, we have to ensure that the basic features of traditional building techniques do not get lost in this transition as they have great heritage value. Profound lessons of sustainability and resilience embody not just the pherols, but also the people of the region who, despite so many challenges facing them, continue to display an indomitable multi-generational spirit and character. The pherols of the Rawai Valley are fine examples of balancing environmental resilience with ecological harmony and timeless beauty. They need to be conserved, studied and, most importantly, recognised as potent pointers on how to create a regionally-specific architecture and community.

All photos: Harshul Singh and Ekangsh Agarwal, students of Graphic Era Hill University, Dehradun, India

Comments (0)