Rao Jodha Desert Rock Park started out as an unruly tract of rocky land adjoining Mehrangarh, Jodhpur’s iconic fort in India’s western desert state of Rajasthan. The land belongs to the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, which manages the fort as a museum, and, in 2006, the Trust invited me to ‘green’ this area as an adjunct to the fort and that’s when I first went to take a look at it.

It was both appalling and exciting. The land was intensely rocky, made up of crystalline volcanic beds that originally underlay Jodhpur’s marine sandstone. All the softer sandstone has been eroded, leaving a gaunt landscape of scarps and lows, steep hills with hardly any soil. It was a rocky wasteland – some 70 hectares (170 acres) in size – overrun by a recalcitrant, stubborn pest of a tree/bush that had edged out nearly everything else. Prosopis juliflora is a South American invasive tree that has wreaked havoc in most hot, dry parts of India. Here, Maharaja Umaid Singh had aerially seeded it in the 1930s as a plant that would green his desert kingdom.

Things didn’t go according to plan and Prosopis juliflora has acquired the name baavlia (the mad one) in Marwari. I knew that the only way forward was first to find some means of getting rid of baavlia and then try to restore the natural ecology of the place, a piece of rocky desert that has its counterpart in about 35% of the Thar Desert. Rock is a lot more ‘difficult’ than sand. I can’t remember if I knew or intuited this fact right away but it didn’t take long to discover, bit by bit.

That was the key. To proceed slowly, gather information and learn from mistakes. Picking up seeds from the right places. Learning how to grow them.

It was no good picking up seeds of plants that grow in sand dunes. They have a completely different set of adaptations and aptitudes. It had to be rock-loving plants: lithophytes.

I sent a short proposal to the Trust, which made it clear that the only practical way forward would be to try and restore the native ecology of a rocky desert. I told them what this might involve: basically, a regimen that had little to do with the usual aims of park making. Scouring rocky parts of the Thar Desert for models to try and imitate and growing wild seeds in huge numbers. I wondered if the Trust would baulk at the idea of bringing back the desert instead of bringing in ornamental trees but to my delight and surprise, after a thrilling wait, I was given the go-ahead.

Contrary to what you might expect, eradicating baavlia proved to be relatively easy only because we found a solution without too much thrashing around. It involved recruiting traditional miners – they call themselves ‘Khandvaliyas’ in Jodhpur – who understood our particular rock (rhyolite and welded tuff) and how to deal with it. They understand the rock through centuries of handed-down wisdom about how it is interbedded, how its fault lines can be exploited and how to carve it up with chisels till they reach at least two feet deep – the minimum depth required to prise baavlia’s roots out of the ground so they won’t coppice again.

Most impressive was that the Khandvaliyas divined the nature of the rock entirely by ear – listening intently to the sound of their heavy hammers as they firmly tapped the surface.

It was virtuoso artisanal wisdom and the Khandvaliyas were magnificent! When I say it was ‘relatively easy’ I don’t mean to belittle their heroic achievement in taking something like 8,000 baavlia trees out of tough, crystalline rock. It was ‘easy’ only in the sense that as soon as we had turned to them for support, we knew the way forward: tree-by-tree.

It took five years to uproot the last of the baavlia but, like I said, we had this issue all figured out by then.

Restoring ecology – any ecology – is never easy. You can’t collapse thousands of years of process into a few years and hope to achieve anything truly meaningful. Knowledge helps. Knowledge of what grows where, of soil types, of ecological gradients. But that was in short supply. Floras of the Thar Desert exist, lists of trees, shrubs, herbs and grasses, but they say precious little about their ecology. Or about natural associations of plants and the kinds of soils they grow in. Or the microhabitats that particular plants are adapted to. Or how to germinate their seeds. So, we were resigned to plodding on with dusty visors, making bloomers but all the while taking furious notes, hoping that we’d stumble on some of the answers.

|  |  |

I’m not going to describe the full process here. Only that we took one fortuitous decision almost by accident, which stood us in very good stead: we decided that baavlia had already done all the ‘research’ for us about where precisely it was possible for a plant to survive in this hostile, rocky environment. We had found the exact spots. And therefore all we had to do was to plant all our ‘big’ plants in pits that had been vacated by baavlia. It proved to be a momentous decision and served us well.

So did note taking. Monitoring how our plants were doing for the first three or four years. Watching to see if there were patterns emerging.Such as, whether or not Ziziphus was doing well in pits that were less than three feet deep or if Salvadora did consistently well if we used mycorhizza in its potting mix.

We followed the patterns. Picked up little tidbits of useful information. (Example: Having a diversity of termites helps. It sounds counter-intuitive but it really does. Like plankton in a lake, termites are part of the base of thefood chain.)

By 2012, seven years had gone by and you’d expect some big results. Lots of tress, billowing canopies... Not so. The park came a long way but things are slow out in the desert. Our growing season was only about six weeks long, so if a kumttha (Acacia senegal) put out five inches of new shoots we learned to be grateful and treated it as par for the course. Our delight centered around the ephemerals that appeared with the first rains, rushing through their short lives so that they could drop their seeds while there was still a little moisture in the ground. Opportunists. Like you have to be in conditions of severe stress.

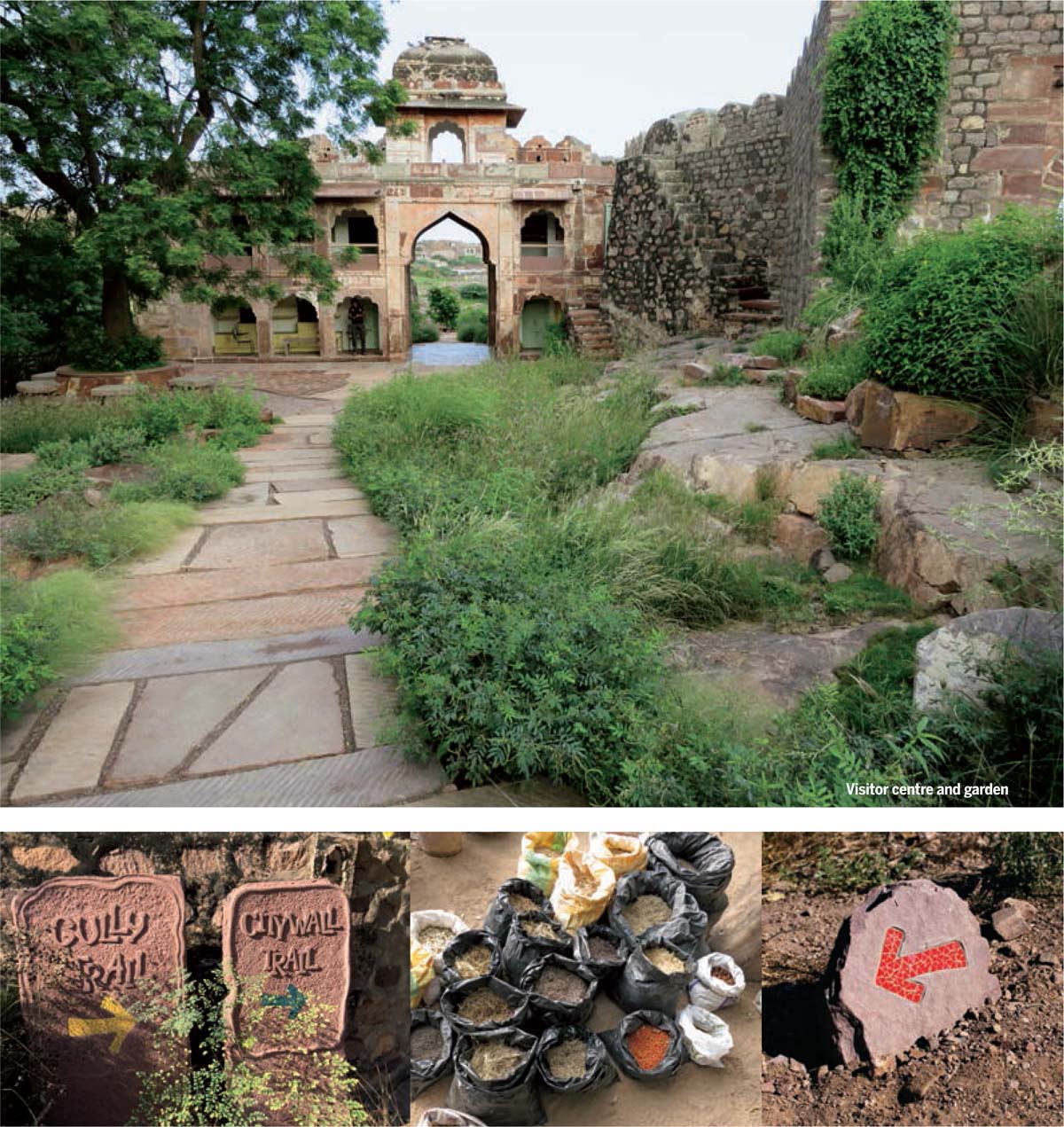

Around February of 2012, the gates of the park were thrown open to the public. Our Visitor Centre is housed in a beautiful but somewhat dilapidated 16th century gateway of the City Wall and, suddenly, it wasn’t just about germinating seeds and watching over plants but creating a welcoming place for visitors. Signage. Exhibits. Field guides. Training naturalists. Even having some rocky landscaping on a human scale in the compound of our Visitors Centre.

Now three years further on, I’m almost ready to say that the business of engaging visitors and showing them a good time has become the prime focus of what we do. And in many ways, it’s proving to be as much of a challenge as creating the rocky landscape. Possibly even more so.

To spend a lot of time and energy creating an island of wild biodiversity in a bustling city might seem idiosyncratic to some. Certainly, the slowness with which Jodhpur’s citizens have taken to the park is an index of their puzzlement.

For the first year-and-a-half, visitors’ entry into the park remained free. We learned that no one values freebies. Local people would wander in and look puzzled. “Kya hai?” they’d ask and our somewhat inept explanations didn’t seem to help. “We’re trying to re-create what you’d see in rocky parts of the desert,” we’d tell them. “It would be too difficult to look after gulmohurs and gaindas here, don’t you see? We’d have to cart in millions of tons of soil and flatten all these rocky knolls...” And though they would nod, they didn’t look at all convinced.

However, not one of our foreign visitors shared any of this puzzlement. It seemed perfectly reasonable to them that we were restoring a stressed ecology to make it look just like it does out in the wild. So, we had to take on board the idea that for most Jodhpuris, the very notion of recreating a natural landscape seems puzzling at best and perhaps even futile and not worth doing.

It’s been a cause of a lot of introspection. Does this have anything to do with the way all our city parks and gardens are in India? That a public park has to have lawns and neatly trimmed bushes and flowering trees? How do you convey the notion to an audience, which has not been exposed to it, that re-created wilderness can be attractive, perhaps even exciting to visit?

Rao Jodha Park started charging an entry fee for adults in 2013-14. Strangely, this had an immediate effect on the number of people coming in. Young people from Jodhpur made up most of the numbers. Some sneaking snoggers were inevitable, but then so were young men who found it exciting to be in a rocky canyon, taking pictures of each other as they scaled big rocks. None of them were still really looking at the strange new plants but maybe this was stage one of ‘taking to’ a wild landscape.

When visitors enter the park and buy tickets, they meet our Naturalists who are available to accompany them on a walk. Most young people don’t wish to spend the extra money (Rs 100/-) on hiring a Naturalist and say ‘No thank you!’

But we’ve found that visitors who do take Naturalists with them nearly always come back with happy expressions. It’s all about learning to see order and adaptability in a jumble of wilderness.

Granite ghost dragonflies roosting on a flat rock. A wryneck in the gravel. A mantid that looks just like a piece of dried three-awned grass. A bright yellow that opens at 4 pm.

For the uninitiated – and unaccompanied – Indian visitor, the park can seem almost completely devoid of interest. One person wrote on TripAdvisor in December 2014:

“Not being a great flora lover I decided to visit the place seeing how beautifully the whole thing was packaged. But to my disappointment there was nothing inside that you can call a park. There were some rough bushes, only rocky terrain, no markings for any plants, no one to assist, no creativity at all. Not worth it.”

Another wrote: “This park is overrated; we went there after reading very good reviews about it. I failed to understand how it could be a tourist attraction. There is nothing to see; ignore this if you don’t want to waste your time.”

For park management, these are useful prods because they point to areas where we need to reach out to people. The vast majority of our reviews are very good, so why then do we have some people who seem so disappointed with what they see – or don’t see – when they go wandering inside the park? It’s easy to ignore these negative reviews as the whining of people who simply have no interest in nature but that would be ducking the question.

We are now engaged in an effort to create signage and information that allows people to do self-guided walks through the park. It’s tricky, because you don’t want to have a natural landscape bristling with signs and manmade objects but we’ve learned that it is possible to create signage that is discreet and complementary to the features of the land and rocks.

At this precise moment – May 2015 – I have to admit that we’re still some way from being able to convince the local people from Jodhpur that the job of creating Rao Jodha Park has been worthwhile.

They know that the Trust has spent a lot of money and that a lot of man-hours have been invested in making the park what it is. But until we can erase that slight frown of puzzlement from their brows, we will not believe we have succeeded in doing what we set out to do.

Photos: Pradip Krishen

Comments (0)