Mountains, women and the weight of water

Water security in the western Himalayan region is met chiefly through natural resources such as springs, aquifers and rivulets, which support livelihoods in the form of agriculture, forestry and animal husbandry. These water resources are increasingly being affected by human interventions, natural disasters and climate change. NITI Aayog, a premier policy think-tank of the Government of India, reported that nearly 30% of the springs in the Himalayan region are dying while 50% are discharging less water due to combined climate and anthropogenic change.

Increasing water scarcity in the mountains poses great constraints on the lives of rural women, who are at the centre of securing water for households. Women spend several hours walking, often making two trips each day, to fetch water and carry heavy bucketloads on their heads. Author Anjali Capila notes that women in the mountains have an inherent knowledge of local conditions as it forms the core of their livelihood, culture and identity. Her study on Garhwal reveals that women share a strong affinity with water and forests (Fig. 1). Their folk songs often describe how deforestation and drying up of water sources affect their daily lives.

The Himalayan region is the source of countless perennial rivers, but the people in the mountains are facing water scarcity at an alarming frequency. In several hilly districts of Uttarakhand, over 60% of rural households depend upon natural resources for their domestic needs. Their drying up causes water scarcity in the summer months. Several studies, such as the climate change atlas prepared by the India Meteorological Department and ‘Climate vulnerability assessment for adaptation planning in India’, highlight that Tehri Garhwal has a relatively high landscape vulnerability in the mountainous regions of India due to climate change. The landscape’s vulnerability originates from reliance on subsistence agriculture and cattle rearing, where water scarcity reduces farm and livestock output, leading to out-migration to cities in search of work.

Out-migration by males makes life in the mountains more difficult for women who make up 50% of the rural population (Census Data, 2011). Women play a crucial role in managing farms and agriculture. Out-migration results in an additional burden while managing household activities, farming and sourcing forest products and water. Water security is essential for sustaining livelihoods, human health and socio-economic development, and has become a central theme of every climate adaptation programme in the mountains. Let’s look at how local women helped revive a drying river and implemented many grassroots solutions, emphasising their relevance in preventing environmental degradation in the mountains through conserving water and natural resources in the Garhwal Himalayas.

Let’s look at how local women helped revive a drying river and implemented many grassroots solutions

Reviving the Heval River’s watershed

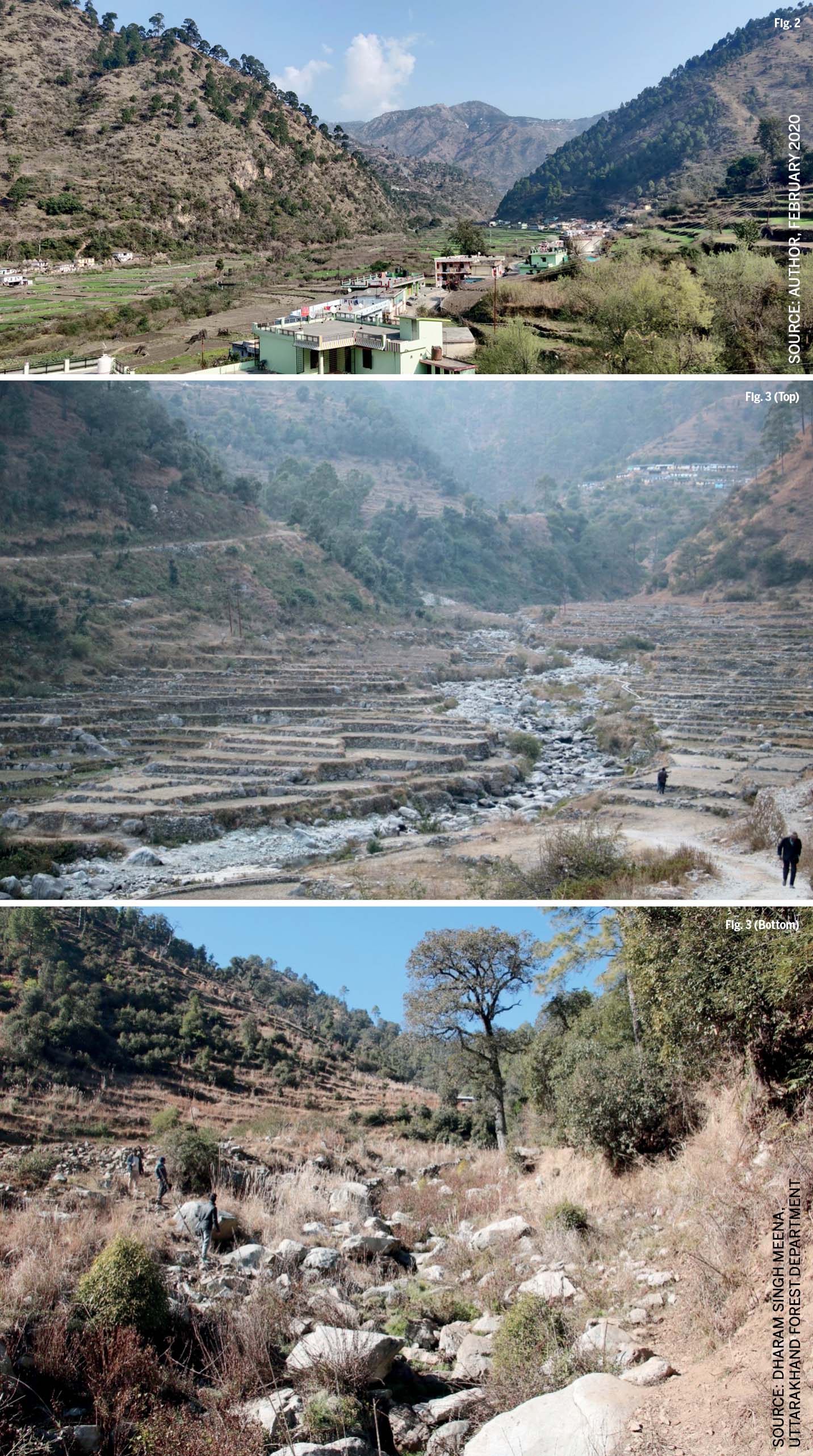

Heval is a 50 kilometres-long perennial tributary of River Ganga in the Tehri district of the Garhwal region in Uttarakhand, India. Heval River’s water catchment area has been severely affected by increased deforestation and climate change (Fig. 2). Springs have dried up and perennial rivulets have become seasonal streams as water output decreased from 84.29 litres per second (L/S) in 2012 to 33.24 L/S in 2018. The declining water resources impact the local biodiversity, increase soil erosion, reduce cropping from four to two seasons, and abandon farming altogether (Fig. 3). These changes began to influence the livelihoods of approximately 100,000 people who reside in Heval River’s water catchment area.

Responding to this acute environmental crisis, ‘The Heval River Rejuvenation Project’ was initiated in 2017 by the local forest department. The project integrates the forest department’s expertise with the local community’s knowledge of water and forests in a participatory approach. The catchment measuring 25,466 hectares was divided into two phases, with a target of reviving 16,168 hectares in its first phase using a hydro-geological approach. Nine smaller sub-catchments were demarcated for detailed surveys, including a forest change analysis and vegetation index from historical satellite data. A detailed analysis identified natural water sources, including 66 springs and 18 streams and potential water recharge zones corresponding to local conditions. Low impact infrastructure such as holding ponds, check dams and chal-khal (percolation pits along slopes) were built with the help of local communities to recharge the groundwater, reduce soil erosion and ultimately rejuvenate the river (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3: (Middle) Dry and affected agricultural terraces near village Pujaldi

(Bottom) Eroded and exposed rock bed and dry rivulets

Clockwise from top left: Percolation pits along slopes, vegetative check-dam made from pine tree leaves, infiltration recharge pits and spring conservation works

Women from nearby villages participated in large numbers to increase the project’s impact and spread awareness about climate change (Fig. 5). Women-led self-help groups look after local nurseries, conduct forest watch, manage community fodder grasslands and afforestation programmes. The forest department and local women and men planted one million local water-conserving tree species on 697 hectares of degraded land. These low-impact actions enhanced water conservation while also helping to restore the ecosystem, resulting in 86.5 million litres of groundwater recharge and generating local employment of 96,085 person-days for villages where most of the beneficiaries were women. Water availability in springs has aided local people in growing income crops and managing soil erosion. Some villages have seen a 30% improvement in productivity and the revived springs along the roadways benefit animals, travellers and inhabitants alike.

Women from nearby villages participated in large numbers to increase the project’s impact and spread awareness about climate change

A revived landscape has several positive consequences on rural women, such as reversing adverse impacts of environmental degradation, increasing the resources for the people, limiting male out-migration and gradually reducing the burden of sourcing water. The Heval River’s rejuvenation has provided local women with an open platform to discuss their problems. It simultaneously empowers them to become stakeholders and decision-makers and aid in landscape management. Women intensify traditional sourcing materials from the forest such as fuel, fodder, grass or forest leaves for making farm manure, hence sustainably re-engaging with forest conservation. Women come forward and participate in community-building activities such as managing nurseries, removal of invasive plants and restoring degraded landscapes. Women are encouraged to participate in skill-building and economic activities, such as operating and managing a business and setting up cooperatives and local self-help groups. Women-led self-help groups have taken over local nurseries, conducted forest watch and managed fodder grasslands and afforestation programmes. They continue to organise awareness camps (Fig. 5) and celebrate special days such as the Hariyali festival, Women’s Day and World Water and Environment Day.

A first of its kind cooperative milk shop and cafe, fully managed and operated by women from the Agarkhal village, has opened its doors to locals and tourists along the Tehri Highway (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Women’s participation is key to climate adaptation programmes Clockwise from top: Women interact with the forest department on suggestions and grievances, participate in afforestation programmes, prepare for their first TV interview on the success of managing and operating the all-women cooperative milk shop

Reviving the kitchen garden

Above the valley of the Heval River, women of Ranichauri and the seven surrounding villages of Chamba, Sabli, Jagdhar, Dargi, Guriyali, Salamkhet and Maun adapt to the climate crisis by harvesting water, conserving agricultural resources and reviving their kitchen gardens. Women of these villages share immense social connections rooted in the tradition of sharing common resources such as water, forests and cultural practices. Since 2011, several pilot projects have focused on the more prominent role of women in the landscape, educating them about climate change and achieving a sustainable livelihood (Fig. 7).

Women from participating households were guided to utilise their kitchen garden or vegetable patch for starting water harvesting and resource conservation. Women were trained to construct their water harvesting tanks in the kitchen garden using cement and local materials such as bamboo for reinforcement and use them with ease (Fig. 8). Based on their capacities and small financial assistance, women constructed their water harvesting tanks, composting baskets, solar dryers and vegetable poly-homes. Each rainwater harvesting tank can store up to 3,000 litres of water and helps grow various local vegetables within the kitchen garden or small fields.

Families with kitchen gardens and poly-homes grow enough vegetables to eliminate the need to purchase them from the market. The surplus produce is converted into vegetable pickles, dried fruits and jams using solar dryers made of local bamboo. Other low-cost technologies such as solar cookers, compost baskets and small biogas digestors help convert the family’s vegetable and agricultural waste into organic compost. Each household can produce approximately 100 kilograms of organic compost within three months. Organic compost decreases reliance on fertilisers and chemicals, lowering crop water requirements dramatically. Several families have switched to organic farming to improve soil quality and raise agricultural yields.

Fig. 9: (Bottom) Grassroot techniques to enhance rural employment. Clockwise from

top left: bee-keeping box and resident bees, new biogas digestor, eggs from small poultry coop

Bottom: The vegetable polyhouse and the kitchen garden grow spinach, radish, mustard greens and peas

The adaptations around the kitchen garden help women lead diversification, improve soil health and increase household incomes. The significant impact is the reduced dependence on the forest for fuelwood, leaves and fodder, enabling the forest to recover and help in water recharge and carbon sequestration. These low-cost and low-impact innovations have allowed women to develop a stronger sense of ownership and shared responsibility for the sustainable management of local resources. They maintain and repair their tanks, compost baskets, solar dryers and vegetable poly-houses. Few low-cost technologies such as biogas have failed to achieve desired success due to high water, cow dung and human inputs. This highlights the fact that rural communities have challenges sourcing raw materials and water for adaptation programmes.

Long periods of adaptation programmes are reviving household incomes, as families reinvest in cattle, poultry or bee-keeping as per individual capacity. The Forest Department has provided several families with wooden hives by recycling fruit packaging. Each beehive, on average, produces about 2 kg of honey over one and half months (Fig. 9). Several women have come forward as farming cooperatives and sell their surplus products such as honey, eggs, pickle and dried fruits in the local markets. As the kitchen garden scales up, it conserves water and agricultural resources, becoming a critical tool for household climate adaption high up in the mountains (Fig. 10).

The adaptations around the kitchen garden help women lead diversification, improve soil health and increase household incomes

Women, climate adaptation pathways and lessons for the future

Current environmental discourse in the Himalayan region focuses on large-scale ecological degradation, the impact of tourism and the ongoing construction of dams and highways. It is also critical to examine the capacities of numerous communities, especially women, who are custodians of managing the landscape, their vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities. There are important lessons to learn from Heval and Ranichauri, i.e., projects that recognise shared backgrounds and existing socio-economic cohesion tend to successfully respond to the climate crisis. These actions show that positive climate adaptation can be nurtured with dialogue and cooperation across scales, and respond to the diverse needs, i.e., livelihood and aspirations, while empowering rural communities and constructing leadership pathways for the women in the mountains. The active participation of women in the environmental rejuvenation highlights their understanding of the impacts of climate change and how they continue to creatively respond to adaptation initiatives and integrate them into their daily lives. Not just enablers of climate action, women of Heval emerge as ‘climate leaders’ by sourcing and repurposing existing natural resources, increasing financial capacity and enhancing food security to improve their livelihood and efficiently adapt to the climate crisis.

Author thanks Shri Dharam Singh Meena, DFO, Narendranagar Forest Division, Uttarakhand Forest Department, Women’s Action for Development (WAFD), Ranichauri, and the women of Heval River valley for their valuable inputs and assistance during the fieldwork.

Comments (0)